Chapter 1: Minerals

What are minerals? How many common minerals you know? Are there others out there that you haven’t discovered yet?

I’m pretty sure that learning about minerals in the first week of geology class is why so many people drop out. Before we could even get into the fun stuff, we had to focus on memorising all these tiny different types of minerals. I mean, who wants to focus on tiny minerals you need a hand lens to look at?

But much like other disciplines, understanding the small stuff (minerals) is actually key to understanding the bigger picture (rocks). Take human biology for example. Our bodies are made up of all kinds of cells—epithelial cells, muscle cells, nerve cells—and each one has a different job. But together, they make up everything that makes us... well, us.

The same goes for rocks. The minerals are the building blocks. They combine in different ways to form the rocks and soils we see around us. So, even though it might seem like we’re getting bogged down in the little stuff, trust me, it’s important. Stick with me here, and let’s dive into the basics of minerals.

Mineral

Elements and compounds that occur naturally and are inorganic form the basis of mineral chemistry. Minerals have chemical compositions that are either fixed or vary within a narrow range, represented by definite chemical formulas. They possess an orderly internal structure, with atoms arranged in a specific pattern, often forming crystals. This unique structure and composition determine the distinct properties of each mineral.

Mineral identification is based on the following criteria:

- Naturally occurring

- Inorganic

- Solid

- Definite chemical composition

- Orderly internal structure

Now you know what minerals are. They are naturally occurring, inorganic solids with specific chemical compositions and crystal structures, which give them their unique properties.

"Is Ice a mineral?"

Answer - Is Ice a mineral?

Yes, ICE is a mineral!

This breakdown reason that ice meet these criteria:

- Naturally occurring – Ice forms naturally in the environment (e.g., glaciers, snow).

- Inorganic – Ice is not produced by biological processes.

- Solid – At standard temperature and pressure, ice is solid.

- Definite chemical composition – Ice has the chemical formula H₂O.

- Orderly internal structure – Ice has a crystalline structure where water molecules are arranged in a repeating pattern.

However, ice is only considered a mineral when it's naturally occurring, like in glaciers or snowfields. Artificial ice, such as the kind made in a freezer, doesn’t qualify as a mineral.

Minerals properties

Minerals have three (3) common properties

- Physical properties

- Chemical properties

- Optical properties

"There are many properties to consider, but these are the general ones we can use for identification."

Physical Properties

- Crystal form

- Specific Gravity

- Hardness

- Tenacity

- Cleavage

- Fracture

- Striation

Chemical Properties

- Acidic Reaction/Effervescence (practical test for carbonate)

- Solubility

- Flame test (observe the color change, when a mineral is heated in a flame)

- Bead test

- Fusibility

- Open and Close Tubes

Optical Properties

Note: In this section, 'optical properties' do not refer to petrographic properties but rather to characteristics that can be observed with the naked eye.

- Diaphaneity

- Color

- Streak

- Luster

- Play of color

Other Properties

- Odor

- Taste

- Feel

- Magnetism

- Fluorescence

- Double refraction

In detail, I will write additional posts covering the properties later (including minerals' physical and chemical classifications), as there will be too much information to absorb all at once.

As mentioned above, these are just the properties of minerals.

But how can we group them?

Minerals group

We can't classify them based solely on their properties because properties are just expressions that help identify minerals—they don't provide a proper grouping. So, we need to return to the basics of minerals.

We know that minerals are made up of elements and compounds, which, in common chemistry, consist of a cation (positive ion) and an anion (negative ion) or a complex anion. Therefore, we will group minerals based on their chemical composition, specifically by the type of anion they contain.

It might start getting a bit boring, but I still want to add more informative details to make your brain freeze for a moment. Now, it will be more intensive information.

What is the most common minerals in the earth crust?

The Earth's crust is mostly made up of two (2) types of minerals: feldspar and quartz.

- Feldspar: This is the most common mineral, making up about 41% of the crust. It is a group of minerals that includes both plagioclase and alkali feldspars.

- Quartz: This is the second most common, making up about 12% of the crust. It is made of silicon and oxygen.

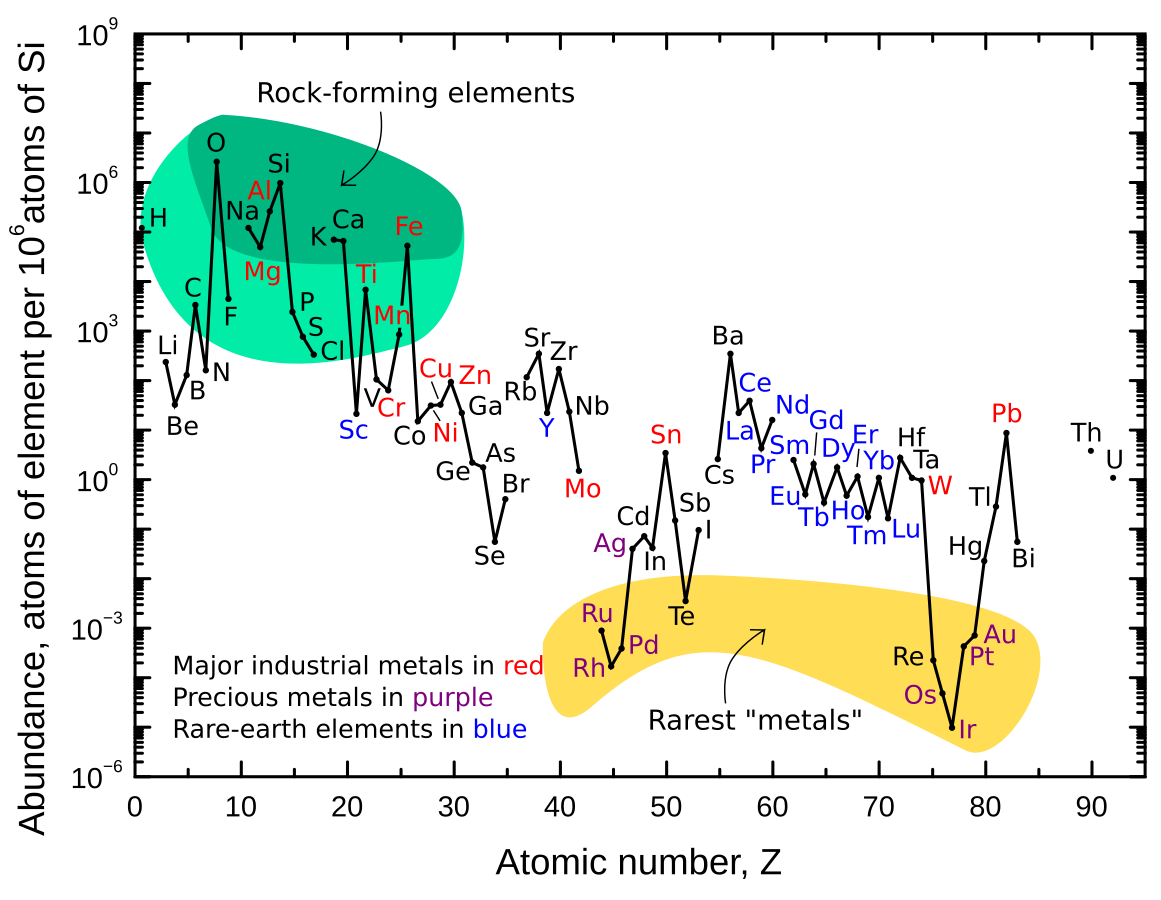

The main elements that form these minerals are:

- Oxygen (46.1%)

- Silicon (28.2%)

- Aluminum (8.23%)

- Iron (5.63%)

- Calcium, Sodium, Magnesium, Potassium, and Titanium are also present in smaller amounts.

"I tried to search for general information and came across this from the USGS on Wikipedia. I understand the need for reliable information, but since this is just an introduction and general overview, it’s not something that could be twisted into a conspiracy. Therefore, Wikipedia is reliable for this information as it is sourced directly from the USGS."

Now, as you can see, minerals are abundant, with Feldspar and Quartz being the primary components of Earth's crust. These minerals belong to the silicate group. Let's get back on track with grouping them.

In general, we can categorize minerals into eight (8) main groups:

- Oxides: Minerals composed of elements combined with oxygen. Examples include hematite (Fe₂O₃) and magnetite (Fe₃O₄).

- Sulphates: Minerals containing sulfur and oxygen, often combined with metals. Examples include gypsum (CaSO₄·2H₂O) and barite (BaSO₄).

- Sulphides: Minerals composed of metal elements combined with sulfur. Examples include pyrite (FeS₂) and galena (PbS).

- Halides: Minerals composed of a metal and a halogen element (fluorine, chlorine, bromine, or iodine). Examples include halite (NaCl) and fluorite (CaF₂).

- Carbonates: Minerals containing carbon and oxygen, combined with a metal. Examples include calcite (CaCO₃) and dolomite (CaMg(CO₃)₂).

- Phosphates: Minerals containing phosphorus and oxygen, often combined with metals. Examples include apatite (Ca₅(PO₄)₃(F,Cl,OH)) and turquoise (CuAl₆(PO₄)₄(OH)₈·4H₂O).

- Silicates: The largest and most complex group, containing silicon and oxygen, often with additional elements. Examples include quartz (SiO₂), feldspar, and mica.

- Native minerals: Minerals composed of a single element. Examples include gold (Au), copper (Cu), and sulfur (S).

"If you want to explore further, the Australian Museum categorizes minerals into eighteen (18) groups plus silicates, as shown in the link below."

"The first time I studied geology, it felt like a boring dive into the fundamentals and chemical properties of minerals. However, as I learned more, I began to realize how many of these minerals are present all around us, often hiding in plain sight."

For example, just look at the Sandstone or granite floor beneath your feet or counter bench or some of the building blocks or behind your backyard—it’s not just a construction material but a natural mosaic of quartz, feldspar, and mica. Each crystal tells a story of its formation deep within the Earth over millions of years. Once you start noticing these details, the ordinary becomes extraordinary, and the world around you transforms into a gallery of Earth’s natural artistry.

I use GRANITE ('gran·ite' - noun) as an example because it contains large crystals that are easily observable. These crystals, like quartz, feldspar, and mica, are visible to the naked eye, allowing you to appreciate the intricate textures and composition of this igneous rock.

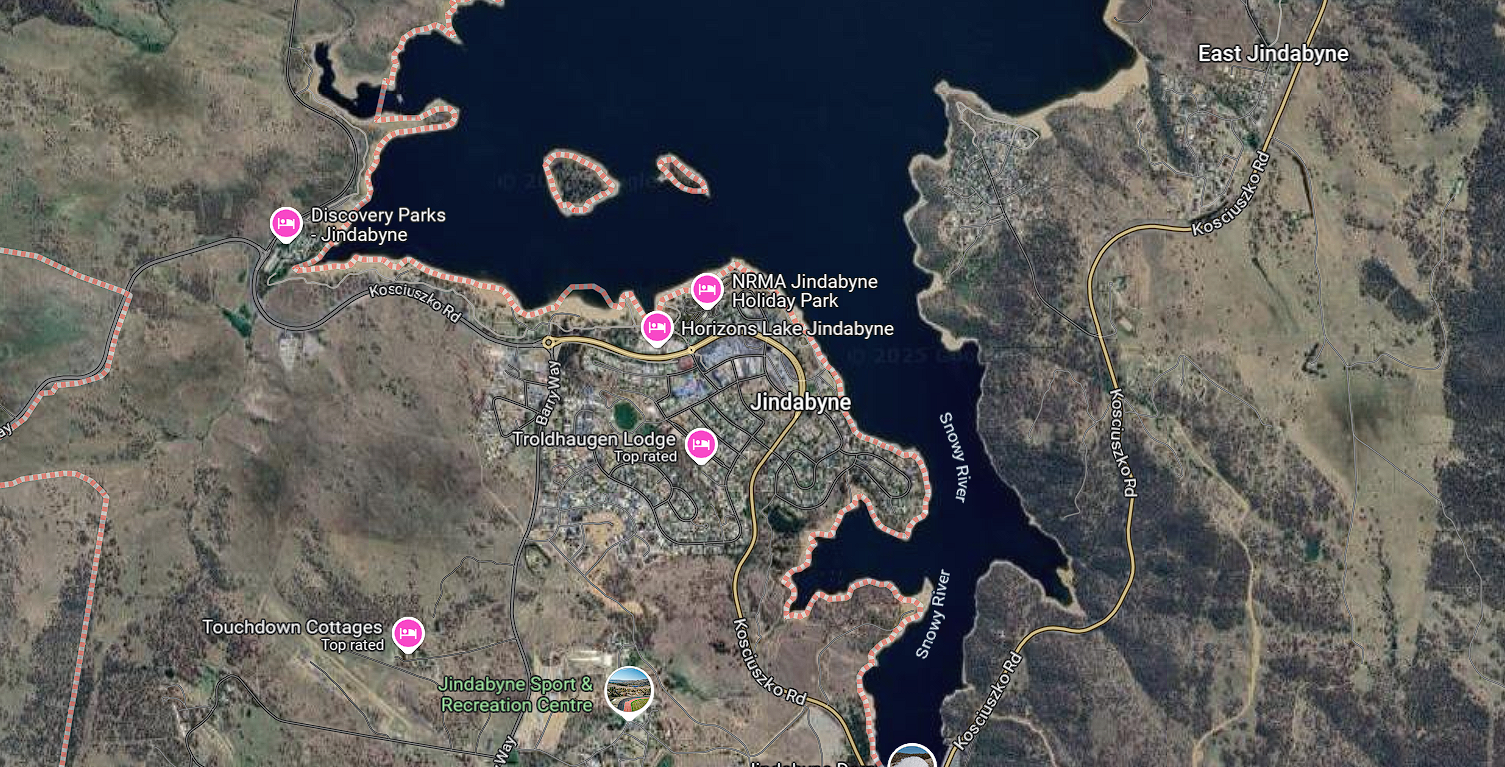

"If you're in Australia and wondering what granite looks like or want to observe the nature of a granitic batholith, I suggest visiting Jindabyne, NSW. You can enjoy a beer, watch the serene Jindabyne Lake, and soak in the beauty of the snow during winter."

Subscribe, Like and Share

"Show people the beauty of the Earth through your eyes."

Member discussion